Things I've Done: Maxwell Plus

It’s taken a long time to write this. Not because it was a secret but it has taken me about that long to decide what I wanted to say. The short version is that Maxwell Plus was an AI startup in health that we ran for six years, ending July 2022. We shipped product, helped find 35 cancers and learned a lot along the way. There are plenty of ways to tell any startup story and no matter what I put down some pieces will be left out. I’m glad I did it, there’s stuff I’d do differently but nothing I regret.

I’ll caveat the below that most of the dates and timeline are based on emails and photos on my phone. I may have mixed up a couple specifics but the story remains the same. There will be details missing both intentionally and not.

Now for the long version.

2016 - Genesis

Things started in March of 2016. At the time I'd submitted my PhD thesis and had spent a few months doing odds and ends in software consulting. I was ready for whatever came next but wasn't sure what that would be. I knew a lot about medical imaging and enjoyed making software. I'd run a startup a couple of years before the local startup scene had evolved enough that taking another run at something was more plausible than ever.

One afternoon I was at River City Labs, a local co-working space, enjoying a beer or two after an event. I got to talking with Steve Baxter about the work I had done during my PhD. During that conversation at some point Steve commented that he wished he could get a head-to-toe MRI scan every so often just in case there was something wrong that was too early to be picked up via symptoms. With two beer gusto I proclaimed that I could definitely build something like that before moving onto whatever we talked about next.

A couple of days went by and I hadn't given the conversation much thought. Steve on the other hand, had been thinking about it. He called me and asked if I had meant what I said. After remembering exactly what that was I said I would ask a few questions and see what made sense. I knew the analysis part was probably technically possible but getting a whole body MRI was pretty uncommon and likely for good reason.

The revisions for my thesis came back so by coincidence I booked a meeting with my supervisor.

I asked him what he thought of the idea. His reaction was blunt. It was possible but good luck finding a doctor who would agree to read a full body MRI. If they read it, it's on them not to miss things. Plus booking time to get a well aligned MRI from head to toe would have been tough, even in an academic context. I left thinking it sounded hard but might be worth a little more digging before calling the whole thing off.

Just in case it helps, remember this was 2016. ResNet came out in 2015, AI was very early in its current hype cycle.

I spent some spare time between consulting projects testing ideas. I found the Cancer Imaging Archive and downloaded a dataset or two to see what I could make work. The results were alright. I had a single GPU so progress was slow. I also had no idea about the clinical context of what I was doing at this stage. I knew how medical imaging worked as an engineer but I'm not a clinician.

Matt, a friend who I'd been working with on consulting projects became my co-founder and we continued to tinker around with data and basic models in between paid gigs.

Before long there was enough in what we'd built to get comfortable, but to take things to the next stage we'd need to grow. Neither Matt or I were doctors. We weren't bold (or stupid) enough to pretend we were either. Not knowing many radiologists at the time was a little bit of a vote against taking it further. Despite that, we continued.

Part of that continuation came from a bet. A friend of mine was heading overseas and made an informal bet that we'd not be underway by the time he got back. It was in jest but certainly set a little bit of a fire under me. I figured if it was going to happen I needed to make it happen. Now or never.

I took the plunge shortly after that, post a quick sanity check from the important people in my life. The timing was ideal as the next cohort of an accelerator program I'd wanted to attend was open for applications. Before that though, we needed to bring one or two more people on board. One of the things I knew from the start was that work like this needed more expertise than two founders could provide. Medicine is complex, political and not an environment primed for messing things up. To do that, we'd need a way to pay people.

2016 - Angel Funding and Accelerator Programs

To solve that we decided to pitch Steve on the idea. He’d said in the follow up call that if the idea had legs he’d be interested in supporting it. We put together a pitch deck representing what we’d learned so far and where we thought we could take the idea. The pitch deck was heavy on the theoretical and lots of the product was described in Google Slides clip art.

The idea, as we saw it at the time, was to take regularly spaced full body MRIs. We’d have each one looked at by an expert but importantly, build a view of how your body was changing over time. With enough samples we hoped to distinguish between the kind of changes that were part of normal life and those that were early signs of something more serious.

We knew even then that the ‘whole body diff’ would need a tonne of data so we set ourselves up to also focus on a couple of key and common cancers as a starting point. We looked at breast, prostate, lung and brain cancers as early candidates. All four are common and have fairly distinctive patterns of change on imaging.

The pitch went well. I try, when there’s ambiguity, to lean towards reality rather than over-selling something. In my mind, while there’s a definite place for sales and hype, medicine is not the industry to flex that muscle too hard. This applies doubly so in terms of investors. Medical startups take a long time to grow and you’re going to be working with your investors for a long time. They need to know what is really going on if they’re going to help.

We secured a small round, enough to ensure we weren’t working side jobs to pay the bills and to bring on our first engineers. In today’s world, and in the context of your typical US fundraising round you’d probably call it pre-seed, maybe something smaller. We didn’t have a product, we had an MVP of an MVP and a plan to make things happen. I’ll always be grateful to Steve for taking the punt on us.

With a little bit of cash in the bank we started working on fleshing out our product. We started scouring the web for accessible, free and appropriate data to use. There’s a lot out there if you know where to look and our initial use case was broad enough that we could pull in just about any MRI data we could find. We managed to amass around 1,000,000 scans of various types from lots of different data sets. It’s a credit to the research community that so much data is available for other people to use.

We leveraged our new bigger data set and some first-pass AI models as our path into the accelerator program. The program was a joint program between a local co-working space (River City Labs) and the Australian telco Testra, run under the name Muru-D.

From memory Muru was a word meaning ‘coming together’ and the D was for ‘Digital’. I don’t know if many people knew that though. This was December 2016 and we were the second cohort through the program and had heard good things form those that came before.

For anyone more familiar with the international accelerator scene, the Muru-D program was good but not great. There were some excellent people across both the teams and those running the show but the reality was (and still is) that Australia is small and startups are still a little obscure here. Compared to something like Y Combinator or Techstars, the program was pretty basic. Nevertheless, it gave us a cohort to be part of and the accountability we needed to keep moving forward.

Two early milestones we set for ourselves were to position ourselves for another round of funding and to find ourselves a chief medical officer. We knew that to be taken seriously in the medical space we couldn’t rely on just hiring good engineers or salespeople. We needed someone with deep expertise in the clinical application of what we were doing.

Over the first six weeks of the program we talked to dozens of potential candidates, eventually narrowing it down to a small handful. After a few more rounds of discussion we brought on Dr Peter Swindle as our CMO. He was a urologist who ran a private urology clinic full time and had a particular interest in medical imaging. He joined in a part time advisory capacity but brought with him some much needed medical credibility.

Looking back, there’s part of me that thinks we probably should have looked for someone wanting to join full time. Dr Swindle wasn’t in a position to give up his clinical work and provided us with plenty of guidance but there is something different about having someone part time and full time. A full time position, especially that early in a startup, shows a certain level of commitment that’s hard to match. As I mentioned at the start, this isn’t something I regret, but if you’re looking to hire a CMO yourself, I strongly recommend finding one who’ll join full time.

At the time we were a team of six. Me and my co-founder, three engineers and our CMO. We were making slow and steady progress on the technology front, building a collection of segmentation and classification models based on the data we had. We were starting to see the edges of our current dataset and the need for a focused, high quality dataset.

In January of 2017 the accelerator took a trip to SF and NYC as a part of the program. We’d meet with investors, other startups and expose ourselves to a much more thriving start scene. Our goal was to meet with some US investors and potential collaborators.

The trip overall was fun and interesting but two things in particular stand out in my memory. One was a very odd meeting with a team at SAP and another was a pitch competition we won.

Starting with the meeting with the guy at SAP. We hired a car and drove out to their campus. I can’t remember how we setup the meeting in the first place but it was with their newly formed AI team. AI was early in that hype cycle and companies were starting to pay attention. They weren’t a company we were specifically thinking about in terms of partnerships but they took the meeting so we went out to see them.

We arrived and spent the first twenty minutes or so talking about what we were doing and he talked about SAP's ambitions in the space. Then we broached the subject of working together. That’s when the meeting turned strange. Very quickly it was clear that unless we could help them in their very exact idea of where AI could help, we weren’t worth talking to.

They, for whatever reason, cared a lot about insurance. Specifically car insurance. They wanted an AI model to look at photos from accidents and predict what claims could be made. Miles away from medical diagnosis. He want as far as to try and convince us that there was no future for AI in medicine and unless you were directly involved in finance you were screwed.

We were polite and left but I still think about it sometimes. I don’t see the meeting as a reflection on SAP as a whole but it was the theme of the moment. Everyone had their idea about how AI was going to make them rich and the tunnel vision of not looking beyond it. It would be a year or so until people started to realise that being collaborative was better than aiming for a made up winner takes all.

The other thing that’s stuck with me was a pitch competition we won. It was an event we found on meetup run by a local startup group. It was mostly something to do on an otherwise empty evening. What stuck with me wasn’t that we ended up winning but how hollow that felt.

It’s easy to get caught up in the rose coloured tint of early startups. Everything seems cool and exciting and if you’re not careful you can lose sight of the fact that you’re not there to be in a startup, you’re there to build a real business that solves a real problem.

Winning that competition didn’t really mean anything, other than we were pretty good at telling a story. I am glad I saw that for what it was. It helped reinforce the need to focus on what mattered. That isn’t to say those things are pointless, they can be fun, but they’re not an indication of success, despite what the even description might tell you.

2017 - Our Seed Round

Back from the trip we had another month or so of the program. We made the call to focus specifically on prostate cancer as a first product. It aligned well with our new CMO and meant we could use our fairly limited resources more effectively. Our goal was to build an MRI specific tool to help find and classify potential cancers.

We merged together the various data processing scripts and AI models we had into the first version of our platform. Our tech stack was a Django backend, a React front end and a work queue that pulled data and ran it through our in house Tensorflow models. We kept a very similar stack for the remainder of the company. We eventually looked at other front end setups as we shifted to mobile but all things behind the scenes continued to grow from that initial stack.

Without going too much into the pathology of prostate cancer, its a disease that typically effects older men and there is a very high rate of low risk and slow growing cancer. There’s a lot of controversy in the clinical world around whether we should test for prostate cancer at all. Our thesis was that technology could help find the high risk cases and rule out the low risk ones, making the clinical statistics more favourable to widespread testing.

After making this decision we applied to join the Reimagine consortium. This was an international study looking to find new ways to diagnose prostate cancer. They had a particular focus on MRI which aligned well with what we were doing.

It was an interesting group to be a part of but ultimately ended up being very slow. By the time things wrapped up in 2022 they still hadn’t released the first batch of data to participants. This isn’t unusual in the world of large scale clinical trials but it does highlight that research and startups can often move at very different speeds.

From there we set our sights on raising our seed round. We were going to need more cash to get a product built, validated and through the regulatory hurdles needed to go to market. We started pitching Australian VCs hoping the find the right match.

In my experience, all fundraising is a numbers game. No matter how good things are you need to talk to a lot of people to find the right match. There’s a need to refine your story but its also important to find the right partners. You might find someone keen to be involved that doesn’t align. It’s hard to list all the ways that investors might not be the right fit but its one of those things where you’ll know when you’ve found the right ones.

For us, that match came with Main Sequence Ventures. They were brand new when we met them. They hadn’t finalised their fund yet but they were a spin out fund from Australia’s peak science body the CSIRO. They were focused on deep tech startup, especially where there is collaboration between startups and public research.

Because they were so early in their fund the conversations continued while we talked to others in the market. We had mixed interest overall, part of it came form the timeline needed to bring medical technology to market and other parts came from just being early in our development.

Along the way we met other interested parties but ultimately it was MSV that led our round. They partnered with the Queensland Business Development Fund which was a state based fund aimed at brining more startups to Queensland.

With the round closed we started to shift from a small group of people to a fully fledged company. We leased an office, grew our team and set to work on product.

We grew headcount fairly quickly, mostly in our engineering function. We were working on our core product and the associated AI models and in parallel tried to test some ideas around potential business models.

We knew that there was a path to being a tool used by clinicians, specifically radiologists, as part of the diagnostic process but we set our sights on something bigger. Within prostate cancer, and many other clinical pathways, there are many doctors and a whole lot of data involved in getting to a definitive diagnosis.

We wanted to find a way to assist in the entire diagnostic flow. If we just sold to radiologists we’d only have the MRI on hand but we felt that if we had access to other data we could better predict risk. This ultimately ended up working well for us but at this stage it was still very much untested.

To test this idea we ran a small test in a less clinical setting. We worked with a small group of people to get some basic blood tests, a DEXA scan and some other general tests. We processed the results, reviewed them with a doctor and gave them some high level advice on improving their health. It wasn’t aimed at being diagnostic but we wanted to test if people would engage with healthcare delivered this way.

It was fun, it gave us some interesting feedback on how to delivery B2C healthcare but we left it alone after that. Ultimately it was an experiment to test and idea and we weren’t looking to shift away from diagnosis into the more light tough ‘wellness’ space.

2018 - Change

By this time we were in 2018. That was a packed year for the business. While we continued to work on our product and company a lot happened that shifted who we were.

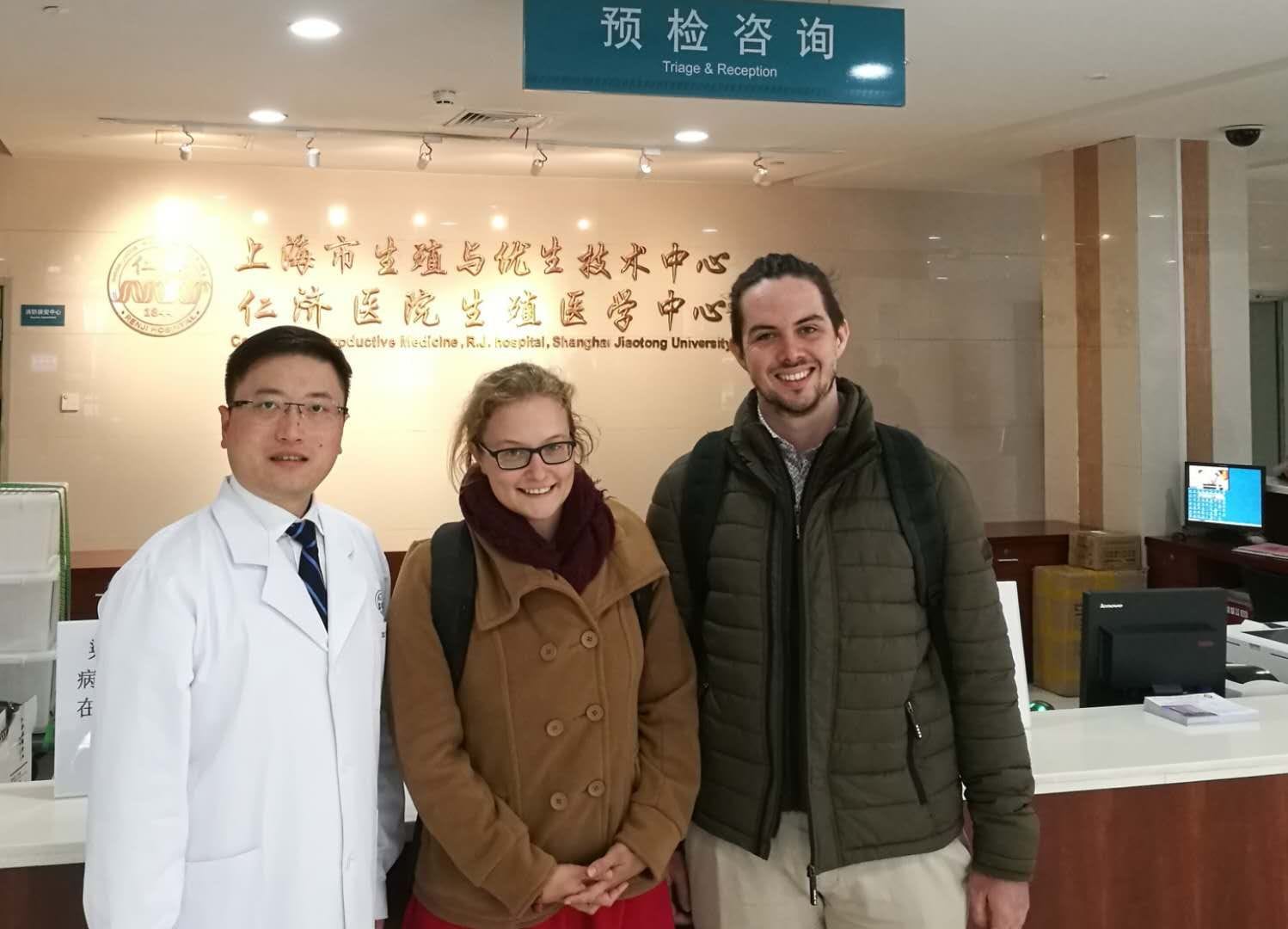

The first of these was a trip to China. We signed up for a trip run by the government for Australian companies looking to expand into China. For us, we were at a stage where it was clear we were going to need a lot of data. There are hospitals in Shanghai that do more prostate cancer surgeries in a year than the whole of Australia so we figured it was worth exploring to see if we could work together.

China also had (and may still have) special economic zones specifically aimed at medical innovation. Within those areas, companies could apply for accelerated regulatory approval just in that one geographic area. We thought this would be an interesting way to test launch our product if all things aligned.

We met with a number of hospitals and groups in China but ultimately the realities of working in China without being a Chinese company proved too much of a barrier for the return we expected.

Then, later in the year, my co-founder left. His partner was moving to the UK and while we went back and forth on being long distance founders, ultimately he decided he wanted to step back and start fresh in the UK.

It was a strange time. I won’t pretend it was simple or easy or free from complicated feelings but ultimately I think it was for the best. He’s been doing interesting things since then with a number of different companies in the UK.

A few months later, my good friend Tom joined the company. Without putting too much pressure on it in the beginning I was looking for someone to step into the gap Matt left when he moved on.

Tom did his due diligence before joining. We chatted a lot over several months about my plans for the company and how we were going to get there. At the time he was working at a top tier consulting firm so leaving to join a startup was no small ask.

Tom eventually did join the company and was there from 2018 until the end of the company. I wouldn’t have been able to do it without him and the next business I start I hope he’ll be there on day one this time.

Later in the year we went back to the US. This time it was to meet with potential clinical collaborators. I started the trip with a conference in Nashville and then spend time in California and New York talking to doctors.

We built a strong network of collaborators but it was becoming clear that within the world of US medicine, if you’re not in the US you may as well not exist. Being in Australia was equivalent to being on a tiny island like Fiji.

I’ve given this advice before but one thing I would recommend to anyone building a health company in Australia is to think long and hard about moving to the US on day one. Things move faster there and it is a lot easier to move from the US to the rest of the world than to start elsewhere and pick the US as geography number two.

At around the same time that year we also started work on a joint research partnership. This was in the form of a ‘Cooperative Research Centre Partnership’ or CRC-P grant. The purpose of these projects was to link public research to commercial companies with a focus on brining research to market.

We partnered with i-med radiology group and a team at the CSIRO to start commercialising an algorithm to quantify amyloid plaque on PET scans. The goal was to take a previously subjective review process and normalise it with a quantitative measure. This would help both in diagnosis and in monitoring of treatment effectiveness.

There’s a lot of controversy in the Alzheimer’s world around the link between amyloid plaque and Alzheimer’s. We weren’t there to weigh in on the argument one way or another, amyloid plaque is unquestionably a real phenomenon and tools like this could assist in proving, or disproving, its link to Alzheimer's.

The project spanned the next three years and while the company ultimately wound down before we could bring the tool to market, we were able to advance the technology along the way. Funding for the project covered two post doctoral positions and two PhD positions at the Queensland University of Technology.

Working with the Post Docs and PhD Students was my favourite part of the project. It gave me a chance to reconnect to academia in an arms length way without it becoming a major distraction to growing a startup. It also gave me a chance to be on the other side of the PhD supervisor table, this time as an industry advisor.

Looking back I probably wasn’t the greatest advisor. Running a startup is a busy job and I don’t think I made myself as available as I should have. In the grand scheme of things, that probably didn’t matter as I was only a minor part of their supervisory team but I do look back and think I should have allocated a little more time. Both students have now graduated with interesting PhDs focused around AI and its applications in medical imaging.

It was around this time that we also started working towards publishing our own research work. As a medical device you need peer reviewed results to both be taken seriously and to achieve regulatory approval. Whenever we published a paper we were working with external collaborators to minimise any bias in our work, and to help build our clinical network.

We published at conferences and in journals. In both cases we made the call to focus on clinical publications rather than technical ones, our goal was clinical impact and not clever engineering and we wanted our output to reflect that.

2018 - Regulatory Approval

Towards the tail end of 2018 we also had our first regulatory audit. We’d chosen to pursue CE certification as a first step. In Australia if you have a CE marked device you can put it onto the ARTG, our register of medical goods, without needing an additional Audit in Australia. This would give us access to two markets, Europe and Australia, fairly quickly.

The scope of our audit covered two separate products. One was a Class I device which patients used to receive results and communicate with clinicians. The other was a Class IIA device which processed the data and provided diagnostic assistance. By that stage we had incorporated data from blood tests, MRI and patient reported demographic information to create a series of diagnostic risk scores at different stages of the diagnostic process.

The audit itself was a monotonous process. Most of all, an audit is a review of process and ensuring that you have met the requirements of the various clinical standards like ISO13485. Auditors aren’t there to run independent tests on your product or functionality, they’re there to ensure you have the right systems in place to build consistent products that meet whatever standard of efficacy you claim. Any verification of efficacy, in our case the accuracy of our models, is done independently in clinical validation studies, the output of which form a part of your Quality Management System (QMS).

What baffled me the most was how little the auditing team understood about software. I am sure they do audits back to back all year long so you can’t expect them to know every kind of product but a lot of the process felt extremely disconnected to a non-physical product. The most direct example I can give of this is their insistence that we review our process around toxicity.

If you’re building a physical product you need to ensure it’s use isn’t going to cause issues if it comes into contact with someone or they eat it. That is not something that makes sense in the world of software. Software may well be eating the world but I promise you can’t get sick from eating software. It took numerous back and forth discussions around this before they were happy to accept that this section was ‘not applicable’ in the context of our QMS.

Tangentially keeping up with medical device regulation since then I can say that it has certainly matured. Even in our later audits there was an increased focus on software specific content like privacy and security which weren’t present at the start. AI itself also now has country specific guidelines and regulation which govern its use in a medical context.

Looking globally we were probably one of the first ten AI products to receive a CE mark so it’s not surprising that regulation hadn’t yet caught up.

The audit took about two days and was a full time process for Tom and I. We worked through the many documents in our QMS. Talked them over and showed evidence that we followed the processes within.

At the end of the audit we received a list of minor issues that we had to resolve and respond to in order to be issued our certificates. I doubt anyone passes an audit with zero minor issues so we touched up our process documents and send back the evidence required and then two months later we were certified. We received certification of our internal quality management system as well as a product specific certification for our Class IIA device.

One then I worried about as we went through the formation and certification of our QMS was its impact on our product velocity. When you’re building an unregulated product you can change direction quickly and ship new features as you need to. When you have a QMS its there for a reason, you need to ensure that what you’re building is compliant and maintains a level of quality in line with the potential impact of shipping a broken product.

To balance this we invested heavily in automation around compliance documentation. We wanted to ensure we could ship as fast as we could while maintaining quality. This became a series of automated tests and reports that would generate prior to every release. We could then review the outputs and be confident we’d maintained correct documentation.

Some processes like risk assessments on new features had to continue to be manual but we worked on large new functionality covered by an initial project level assessment.

I think overall there’s still a huge gap in the market for a tool and process around blending agile software development and medical approval. If someone managed to nail that and productise it I am sure it’d be both lucrative and a path to faster medical innovation. After years of doing audits however, I’ll leave that idea to someone else.

2019 - First Revenue

Once we had our CE certificates the process to list on the ARTG was fairly quick. We submitted our documentation and then we were approved to put our device into the hands of real people.

Our plan, built into the setup of our two approved devices, was to link patients to doctors remotely for analysis of medical data. Our clinical portal serviced multiple clinical specialties but was mostly focused around initial testing and then MRI and potential biopsy.

To make this work well we had a two-sided gap to fill. We needed patients to test and doctors to test them. We felt that without the patient cohort, and some real world experience, we'd have a hard time selling directly to clinicians.

Clinicians are naturally quite skeptical of change and we wanted to first prove that what we were doing would have the impact we claimed it would. Leaning on our experience with our early B2C testing we decided to setup our own clinic.

We hired a GP who would work within Maxwell Plus as the interface between our technology and men who came to be tested. If the patient was high risk, they'd be referred onto one of our specialists.

On day one we just had the one specialist, our CMO. We quickly grew out that network however as we needed more geographic coverage. We leaned on Dr Swindle's connections across Australia to build out a list of around 20 urologists who were familiar with the platform and willing to assist patients who needed further testing.

In the early days we kept our footprint fairly small. We focused on friends and family in the right demographic and worked to make sure the service arm of our business was as high quality as our product.

Part of that meant building a lot of integrations. We needed to be able to gather prior data on patients who signed up. We were able to do so as a service provider by requesting data from a patients pathology or imaging provider but they initially wanted to just send us paper and CDs.

We accepted these initially but it didn't scale particularly well. In parallel we started building integrations into the major providers in Australia. Along the way we learned that despite there being numerous standards around medical data, the actual application of these standards was varied.

Data would come to us in a mix of structured and unstructured formats and we had dozens of parsers to extract useful information and normalise it into something we could feed into our models.

Beyond the basics of data extraction we also had to develop a keen understanding of the many different assays and imaging hardware being used. Each different machine would have slightly different calibration characteristics and we needed to account for those to ensure we were comparing like for like.

I said it a lot then, and I still believe it to be true now, you get a lot more bang-for-your-buck working on cleaning and normalising data than you do building bigger and more complicated models. This probably doesn't apply if you're building a large general model, but application specific models most often suffer from a lack of well formed data.

Once we had data coming into our platform and the clinical team to run it we needed to work out how to sell it.

In Australia, for the most part, general medical expenses are either heavily subsidised or free. This made asking the public for a fee difficult. There was a general expectation that Medicare should be paying for this and patients shouldn't have to get out their wallet.

Being eligible for a Medicare billing code is a very long, complicated and political process. It wasn't something we could let be a blocker to us entering the market.

Instead we tried to anchor ourselves to existing payments in the diagnostic process. In order to assess a patient they had to get one or more tests. We charged a small margin on tests to cover our analysis.

This worked okay, and got us our first paying customers, but it didn't align well with our larger goals. For this model to scale well, we needed to do more tests. Prostate cancer already had a reputation of over testing and I didn't want to align our incentives that way.

We shifted to an annual fee that covered any interactions with our clinical team for a whole year. Tests would be billed externally and outside of our remit. This meant that we were primarily incentivized to see more patients, not to run more tests.

Landing on a price point for this subscription was tricky. For patients who ended up being diagnosed, the value the received was massive. For those that got an all clear, it was harder to justify a fee. We experimented with prices a lot over our time and eventually landed on something that was palatable across the board.

There were plenty of ways we could have maximised revenue across the diagnostic process but longer term we didn't want to only serve prostate cancer patients and we didn't want to setup a business model that didn't scale into a broader medical play.

This is another case where I think we would have had an easier time in another market. I know that some of this is that the grass looks greener in the US but more and more examples of B2C healthcare exist there that justify a higher tolerance for out of pocket prices on healthcare.

We continued to grow and test throughout the year. At the same time we gathered and annotated more data readying our next generation of models. We were seeing moderate early success with our B2C model and wanted to test if we had options in the world of B2B.

In our case we targeted companies with largely male work forces looking to invest into actionable health plans. Industries like construction, mining, engineering and policing tended to have a large at risk male workforce. We reached out and refined our pitch for the corporate environment.

By the end of the year we'd locked in our first B2B sale. A local city council with about 250 men in our target demographic. They'd pay for a year of coverage if we came in and ran some education programs to support the testing.

The program ran well, we say real impact and helped some men who previously hadn't engaged in testing services.

2020 - More Growth and Getting Stuck

We spent a lot of 2020 doubling down on early wins. We'd seen some growth in a number of different areas of the business but none had hit a repeatable process.

During the early months of the year we started reaching out to investors to better understand where we stood in the market and milestones we'd need to hit to raise a Series A.

We found ourselves in an odd position. By entering the market at all we were no long in the world of pre-revenue. Our business was now thought about in multiples of our revenue and projecting our growth.

In some ways, we probably launched too early. We initially went to market in part to prove it was possible and in part because it felt like the right time. Because it was very experimental I chronically under invested in the growth team in the business. We should have invested much more in GTM or made the call to focus on technology expansion more along the path of a traditional deep tech company. Having one foot in both worlds made things tough.

We learned a lot and quite quickly found small pockets of marketing, sales and positioning success that we could double down on. Tom and I set ourselves a goal to do whatever it took to work out how to make growth happen.

I remember weeks where Tom and I would sit and make fifty calls each a day and then spend the afternoons tweaking ads, emails and our on-boarding flow. It was a baptism by fire but during the years we spent in growth we went from nothing to proficient in sales and marketing.

We should have grown out that team and pushed harder but some part of me had started to worry about running out of capital and it caused us to be a little more risk averse than we should have been. Overall though, we managed to get a founder led growth engine up and running. By the end of the year we'd grown from less than one hundred patients to around one thousand.

For us, growth came from good ads and PR. We focused a lot on search ads in the early days, looking to capture men already searching for testing. We spent some time on awareness via social channels and then used PR as a boost to our credibility.

Advertising health services is a carefully regulated process in which we had to ensure we never crossed the line of being overly pushy and encouraging services that people didn't need.

The more men we tested the more evidence we had that the AI powered clinic we were running could potentially make widespread testing for prostate cancer a net positive activity. We ended that year cautious but hopeful that if we could keep things growing just a little longer the clinical results and growth metrics would start to back up the vision we had for the company.

2021 - COVID

If there was ever a tough time to scale an in person service it was 2021.

In many ways COVID awareness and lock downs made people hyper aware of their health. Unfortunately, but understandably, that didn't extend to budding services in an area traditionally considered 'optional'.

We quickly moved our company to be fully remote. It timed well for us with an office renewal and we decided to let the renewal lapse and see how things went. It took some getting used to, as it did for everyone, but we made it work.

Once the initial period of closed clinics and widespread lock downs ended we adapted as best we could to the new state of the medical industry. B2B sales were the most difficult in this period because most of our success there relied on in person events and centralized testing on site. We closed one or two companies over the year but focused more on B2C as it continued to grow.

As the year continued we hit a major clinical milestone. We had enough early diagnoses that we could show our clinic performed better than current clinical guidelines. We were finding cancer that others had missed and better separating low risk cancer and high risk cancer.

We'd need larger numbers to change population level process but we were incredibly proud that the idea we had so long ago had proven itself.

We saw these results after testing around 3,500 patients. In the end around three quarters of them were B2C customers with the rest coming in via our corporate programs. We had enough data at that point to measure churn and saw annual churn rates of less than 7%.

Our tech team had also been hard at work on releasing native apps. Our clinician portal remained desktop focused but most of our users accessed our services on their phones. We'd made the choice to use Flutter for our app development and we released our first test flight version in the second half of the year.

We had built something special here but we needed to raise capital to continue to grow. We'd raised a small extension round early in the year to keep things going during the uncertainty but the last quarter of the year Tom and I focused our efforts on fundraising.

2022 - Winding Down

If you read from the beginning the ending here will come as no surprise. Ultimately we weren't able to raise another round. We were in a no man's land between early growth and repeatable growth and many of the investors we talked to didn't know where to place us in their mandate.

We had some interested parties, went through some round of DD but ultimately couldn't secure the funding we needed to grow. We still had ambitions to expand beyond prostate cancer and work to commercialise technology from projects like the CRC-P and we needed enough capital to continue on that path.

We made the tough call to cut down staff in March or April of that year. We shifted to a small skeleton crew to keep services running and push our remaining cash further. While we had revenue coming in, we were far from profitable at that stage.

As we reached the middle of the year we made the call to end our services and let the rest of the team go. We spent our last couple of months creating a new PDF version of our risk report and generated one for every patient on our platform. This way they'd leave us with a record of all their data and one final assessment they could take to their GP and hopefully continue testing.

We were overwhelmed with the feedback we received when we announced our shut down. Patients sent dozens of heart felt messages about how we'd helped them and their families. Those with diagnosed cancer were expected but many of them came from men who valued the peace of mind knowing they were okay for now.

Middle aged men weren't the easiest cohort of customers to market and sell to but once we convinced them of the benefits they were great users to work with. We spent time with a lot of them over the years as we worked to build out case studies and test new ideas around the product. There's something important about finding customers that you enjoy working with. That's certainly something that's easier when you know you're helping them.

After we wound down, Tom and I approached several parties with an offer to purchase the remaining IP in the company. Those talks were positive but ultimately weren't fruitful. We made the call then to return the capital we had left and de-register the company.

I won't bore you with the long and paperwork filled process that is involved in winding down a company. It took another eighteen months to have it all wrapped up. Not due to anything malicious, these things just have a way of taking their time.

2022 - After

I'd say overall, everyone at Maxwell Plus parted amicably. People were sad, some were annoyed but only because we all felt there was untapped potential left on the table.

One thing that has been a real positive for me in the years since Maxwell Plus is seeing the careers of everyone who worked with us continue to grow. At our peak we were around 25 people and in the years since I've seen people go and do wonderful things. I'm proud of whatever part we played there in being a springboard into the amazing things they have done since.

Personally, it took me a while post shutdown to decide what to do next. Going from full time founder to nothing was a shock to the system. A lot of my identity had been tied up in the business and it was a tough transition. There were days when I felt pretty down about it all and it took a while to come out of that.

Its been almost three years since then and today I look back on everything fondly. There are plenty of war stories. Many of them left out of this retelling but with the benefit of time there's plenty of positive to lock back on as well.

If you happened to read all the way here, thanks. I wanted to write this all down somewhere for my own benefit and figured it might make for an interesting post.

I am fairly confident that this wasn't my final stint at being a founder. Whatever comes next, I hope there's a much longer blog post waiting with a slightly different ending.